FRANKISH CHURCH COLLECTION

The Frankish church is commonly called the "eldest

daughter" of the Western Church, and the body of documents that have come

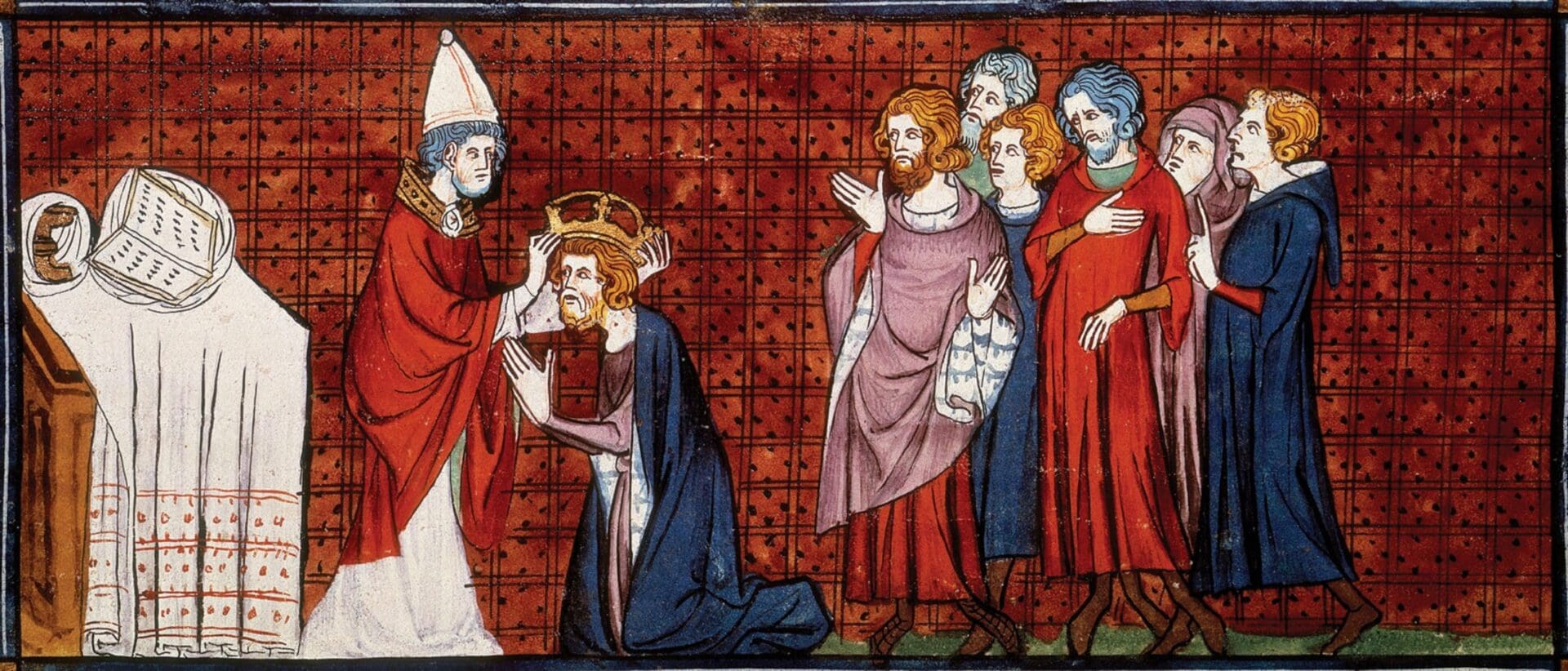

forth from this early period is one of the largest. Just the same, the history of the Church in France during the Dark Ages and Medieval period is one of profound transformation, consolidation of power, and enduring influence on the development of French society and culture. From the early Christianization of the Franks to the rise of the powerful French monarchy, the Church played a central role in shaping the political, social, and religious life of the region. Throughout these centuries, the Church not only acted as the spiritual authority but also became intertwined with the political fabric of France. The story of Christianity in France begins with the Christianization of the Franks during the early Dark Ages. The Franks, a Germanic tribe, settled in what is now modern France after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The pivotal moment in the history of the Church in France came in 496 AD, when Clovis I, the king of the Franks, converted to Christianity. According to legend, Clovis's conversion was influenced by his wife, Clotilde, a Christian princess, and the outcome of a battle in which he promised to convert if he won. Clovis’s conversion to Catholic Christianity (as opposed to the Arian Christianity practiced by some other Germanic tribes) laid the foundation for the Christianization of the entire Frankish kingdom. This was a decisive moment in the history of the Church, as it not only helped solidify Christianity’s position in France but also secured a strong relationship between the Frankish monarchy and the papacy. The Church played a vital role in supporting the legitimacy of Clovis’s rule, and in return, the king supported the growth and expansion of Christianity throughout his kingdom. After Clovis’s death, the Merovingian dynasty, which ruled the Frankish kingdom, continued to support the Church. However, the Merovingians were weak rulers, and it was the Carolingians, particularly under Charlemagne, who would truly elevate the power of the Church in France. In the 8th century, Charlemagne, the king of the Franks, embarked on a campaign to unite much of Western Europe under his rule. In 800 AD, Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Leo III, which symbolized the strong political alliance between the Carolingian dynasty and the papacy. Charlemagne’s reign marked a period of intense church reform and the expansion of Christianity. He established bishoprics and monasteries, and he promoted the spread of Christianity to the Saxons, who had remained pagan. Charlemagne also supported the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of learning and culture, which was closely tied to the Church’s educational efforts.

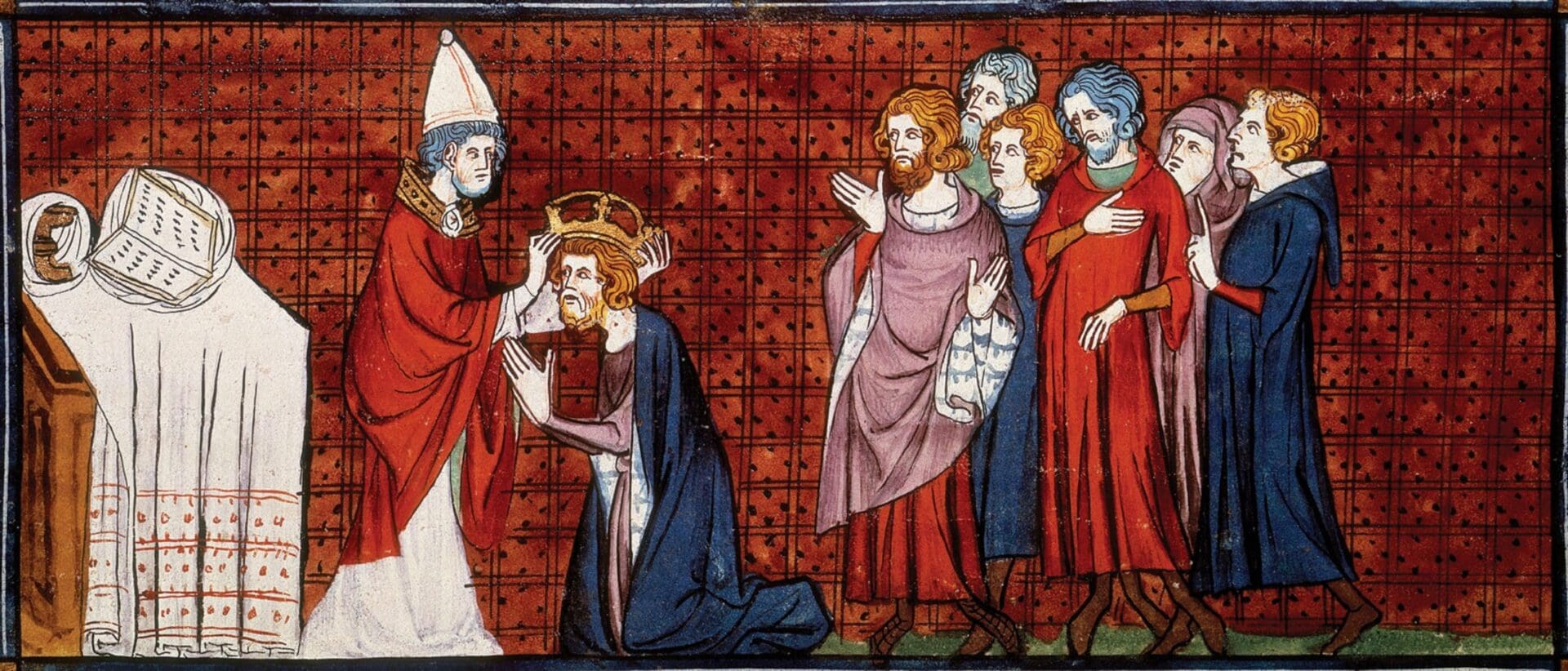

By the 10th century, the Carolingian Empire had fragmented, and the kingdom of France began to emerge as a distinct entity. The Church in France continued to be a powerful force, with bishops and abbots exerting significant influence over both spiritual and political matters. The Capetian dynasty, which rose to power in the 10th century, established a strong relationship with the papacy, ensuring the Church’s support for royal authority. The Cluniac Reforms of the 11th century were an important development in the Church's history in France. Initiated at the Cluny Abbey in Burgundy, these reforms sought to address corruption and laxity within the clergy by emphasizing monastic discipline, celibacy, and the autonomy of monasteries from secular rulers. The movement quickly spread throughout France and beyond, and it played a central role in revitalizing the Church during a time of increasing corruption and social unrest. In the 12th century, the Church in France saw a further consolidation of its power with the rise of the Cathedral schools and the establishment of universities, such as the University of Paris. These institutions became centers of theological and philosophical study, and many prominent theologians, such as Peter Abelard, were associated with them. The relationship between the Church and the monarchy in France was often a dynamic and sometimes contentious one, with both sides vying for influence. However, the Church’s support was crucial for the French monarchy, as the kings of France used the Church to legitimize their rule. One of the most notable moments in this regard was the coronation of French kings in Reims, which became a sacred and symbolic ritual reinforcing the divine right of the monarch. During the 12th and 13th centuries, the Church in France gained great wealth and influence. The Church’s power was particularly evident in the growing abbey system, where wealthy monastic orders like the Cistercians and Franciscans amassed land and resources. The Knights Templar, a military religious order, also gained prominence in this period. The Church’s influence extended into all aspects of French society, including education, justice, and politics. Despite the Church’s dominance, it faced challenges from within, including the rise of heresy and reform movements. One of the most significant heretical movements in medieval France was Catharism, a dualistic belief system that rejected the authority of the Catholic Church. The Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229), launched by the French king at the urging of Pope Innocent III, sought to eradicate Catharism in southern France. The campaign was brutal and resulted in the mass killing of Cathar heretics and their supporters.

The latter part of the medieval period saw the Church’s influence in France challenged by political and social upheaval. The Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) between England and France placed great strain on the Church’s ability to maintain its authority. The papal schism, in which two rival popes (one in Rome and one in Avignon) vied for control of the papacy, further undermined the Church’s unity. Despite these challenges, the French Church remained a central institution, particularly during moments of national crisis. The figure of Joan of Arc, who claimed divine inspiration to lead the French against the English in the Hundred Years' War, symbolizes the deep intertwining of the Church and national identity in France. Joan’s eventual canonization as a saint in 1920 reflects the enduring role of the Church in the history of France. The Church played a central and transformative role in shaping the history of France during the Dark Ages and Medieval period. From the Christianization of the Franks under Clovis to the powerful Church-State relationship in the reign of the Capetian kings, the Church helped establish France as a significant political and cultural force in medieval Europe. Despite internal challenges such as heresies and political strife, the Church remained a defining institution in French life, influencing not only religion but also governance, education, and society at large. Its legacy continues to shape the spiritual and cultural landscape of France today.