JUNE 2024

SURVIVING BYZANTINE IMPERIAL TEXTS

Written by: D. P. Curtin

The corpus of surviving Byzantine imperial texts presents a fragmented and uneven archival landscape. While the Byzantine Empire maintained one of the longest-running centralized states in world history, the textual record of its administration, ideology, and intellectual life is disproportionately scant compared to its duration and cultural output. This discrepancy stems from several interlocking factors, notably the collapse of institutional continuity—especially the demise of the University of Constantinople—the circulation of spurious or highly interpolated documents, and the haphazard survival of many texts in non-Byzantine repositories, such as obscure collections in Italy. The surviving documentation is therefore not only meager but also deeply compromised in its transmission and context, severely limiting the ability of historians to reconstruct imperial thought, policy, or institutional development with precision.

The Byzantine imperial bureaucracy was renowned for its complexity and ritualism, yet ironically, the written records of its operations are often lost or survive in damaged or indirect forms. It should be said that the major problem concerns the lack of continuity in Byzantine institutions, especially following critical transitional periods such as the seventh-century transformation of the Empire into a militarized thematic state and the eleventh-century collapse of the provincial aristocracy under military and economic pressure. Although the court maintained elaborate ceremonial protocols, and the position of the emperor was codified in texts like the De Ceremoniis (ed. Reiske, 1829), such works are rare exceptions rather than representative survivals. Indeed, the fall of Constantinople in 1204 to the Fourth Crusade marked a rupture from which the administrative textual tradition never fully recovered. The so-called "Palaiologan Renaissance" was less a restoration of imperial literacy and more a private scholarly revival. The imperial chancery during this late period produced few texts of lasting significance, and those that do survive, such as chrysobulls or synodal tomoi, often do so in copies preserved far outside the borders of the former empire.

The collapse of the University of Constantinople is emblematic of the institutional disintegration that contributed to the sporadic preservation of texts. Founded in the fifth century and restructured under various emperors, the University of Constantinople served not merely as a school but as a source of bureaucratic training and ideological transmission. However, the university never became a stable, autonomous institution comparable to its Western counterparts. Its curriculum was closely tied to court priorities, particularly in the Komnenian and Palaiologan periods. After the Latin occupation of Constantinople in 1204, the institution either ceased to function or was reduced to an intellectual shell, a fate lamented by figures like Nikephoros Blemmydes and Maximos Planoudes. When higher education re-emerged under imperial patronage in the fourteenth century, it did so without continuity or consistent archives, contributing to the precarious survival of official philosophical and administrative texts. The closing of the university during the Ottoman conquest in 1453 finalized this process of intellectual discontinuity.

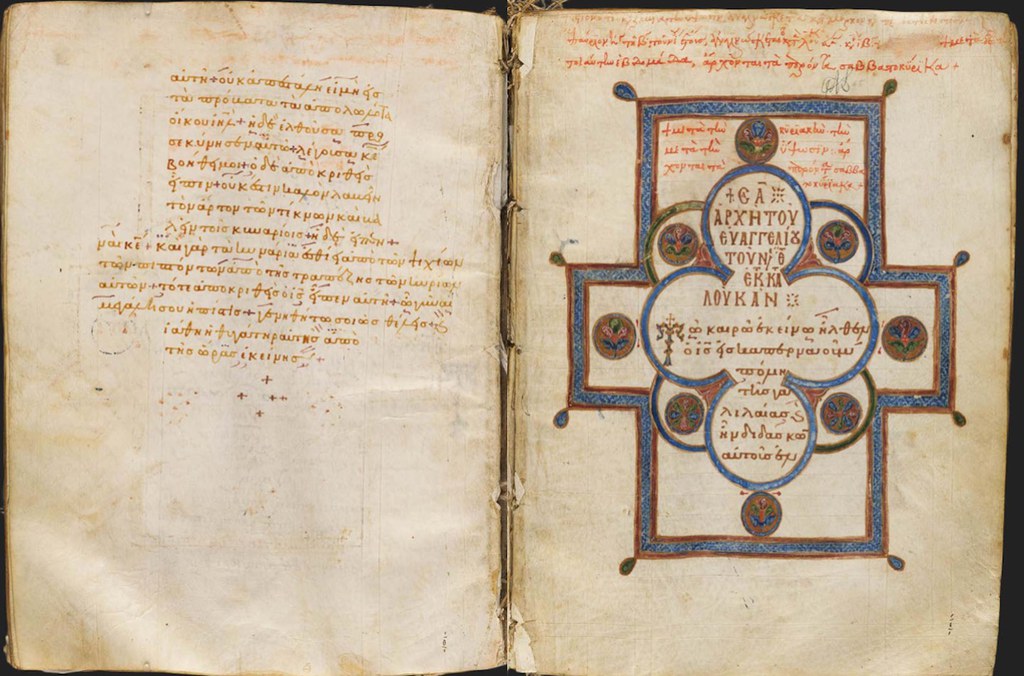

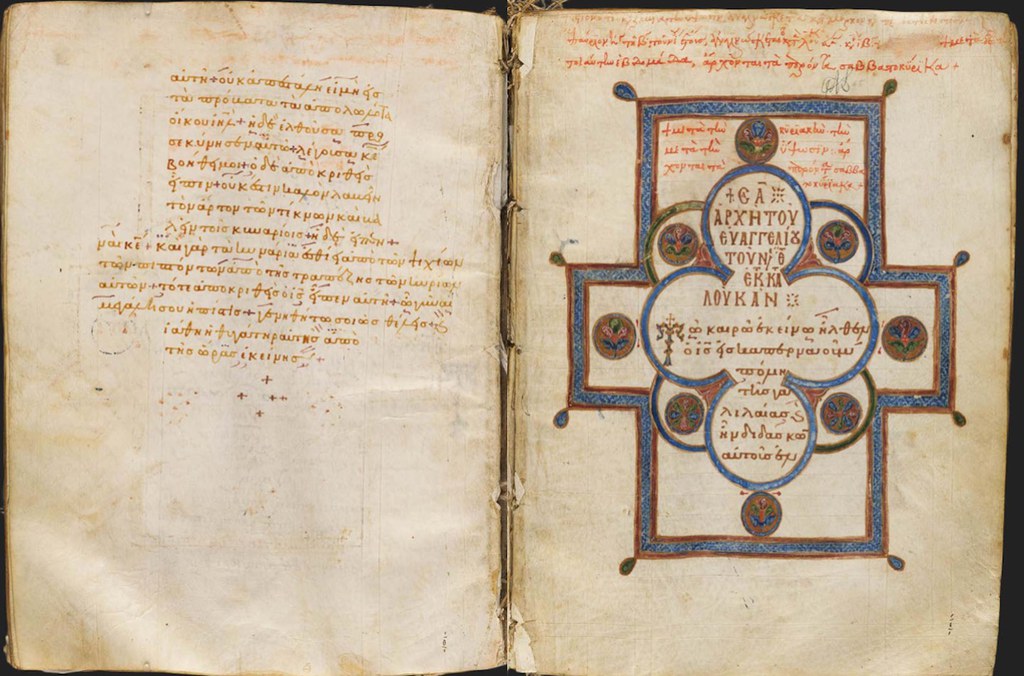

A further complication in the study of Byzantine imperial texts is the problematic nature of many surviving documents. For instance, the Mirabilia Urbis Constantinopolitanae and similar works, while informative about ceremonial and topographical traditions, are often replete with anachronisms and legendary embellishments. Even more troubling are the numerous forged or interpolated texts that claim imperial authority but lack provenance. Some so-called imperial chrysobulls have been shown to be later fabrications, likely created to support legal or property claims by monasteries or Western collectors. The monastic archives of Mount Athos, Patmos, and Meteora contain documents purporting to be imperial in origin, yet their authenticity is often unverifiable. Anthony Bryer and Judith Herrin have both noted how the ambiguous status of many of these texts reflects a larger pattern in the survival of Byzantine literature, in which textual prestige was preserved at the cost of critical transmission practices.

One of the most intriguing and simultaneously frustrating aspects of Byzantine text survival is the manner in which many documents have come down to us not through Byzantine custodianship, but through Western European preservation, often in seemingly random Italian or French repositories. The Vatican Library, the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, and numerous archives in Naples and Palermo house crucial Byzantine texts, sometimes without full cataloguing or contextualization. For instance, the Notitia Dignitatum, though earlier and of Western Roman origin, circulated alongside Byzantine-style imperial directories in Renaissance collections, contributing to confusion regarding administrative continuity. Even texts directly relevant to Byzantine imperial ideology, such as the works of Psellos, Plethon, and Attaliates, were more often preserved and disseminated in Italy due to the interest of humanists such as Bessarion or Manuel Chrysoloras. These individuals carried manuscripts westward, where they were copied and studied more for their classical content than for their documentary or administrative utility.

This process of Western mediation—what some scholars have called the "Renaissance filter"—has had profound implications for the study of Byzantine imperial documents. It has often meant that what survives is precisely what was seen as useful or relevant by Latin scholars, especially those invested in Neoplatonic, Aristotelian, or historical themes. Administrative or bureaucratic texts without immediate philosophical value were less likely to be copied or preserved. This asymmetry in preservation has distorted the picture of Byzantine imperial culture, emphasizing its rhetorical and theological dimensions over its institutional and procedural ones. The result is a corpus that speaks more about Byzantine paideia than about governance or imperial pragmatics.

This fragmented legacy is not only a matter of historical accident but also a consequence of how Byzantium itself conceived of imperial writing. Unlike the Latin West, which developed a robust and often juridical documentary culture (as evidenced in the papal chancery or Carolingian capitularies), the Byzantine Empire maintained a more symbolic and performative approach to texts. The authority of a document derived not so much from its textual content as from its ceremonial function and physical characteristics—such as the presence of the imperial signature (menologion), the golden seal (chrysobullos sphragis), or its public reading in synod. When these performative contexts vanished, the texts themselves often lost practical relevance, becoming vulnerable to neglect, reuse, or spoliation.

In recent decades, new methodologies in codicology, digital paleography, and comparative philology have begun to shed light on the scattered fragments of this lost world. Projects such as the Dumbarton Oaks Hagiography Database and the Vienna-based Tabula Imperii Byzantini offer modern scholars tools to reconstruct contexts that had long been assumed irretrievable. Nonetheless, the fundamental problems persist: a lack of institutional continuity, the collapse of Byzantine higher education, the proliferation of dubious documents, and the accidental nature of manuscript survival continue to limit the field. The Byzantine Empire, once among the most textually sophisticated societies of the premodern world, thus leaves behind an imperial record that is both tantalizing and tragic in its incompleteness.