JUNE 2025

OPEN CRITIQUE OF THE PATROLOGIA GRAECA

Written by: D. P. Curtin

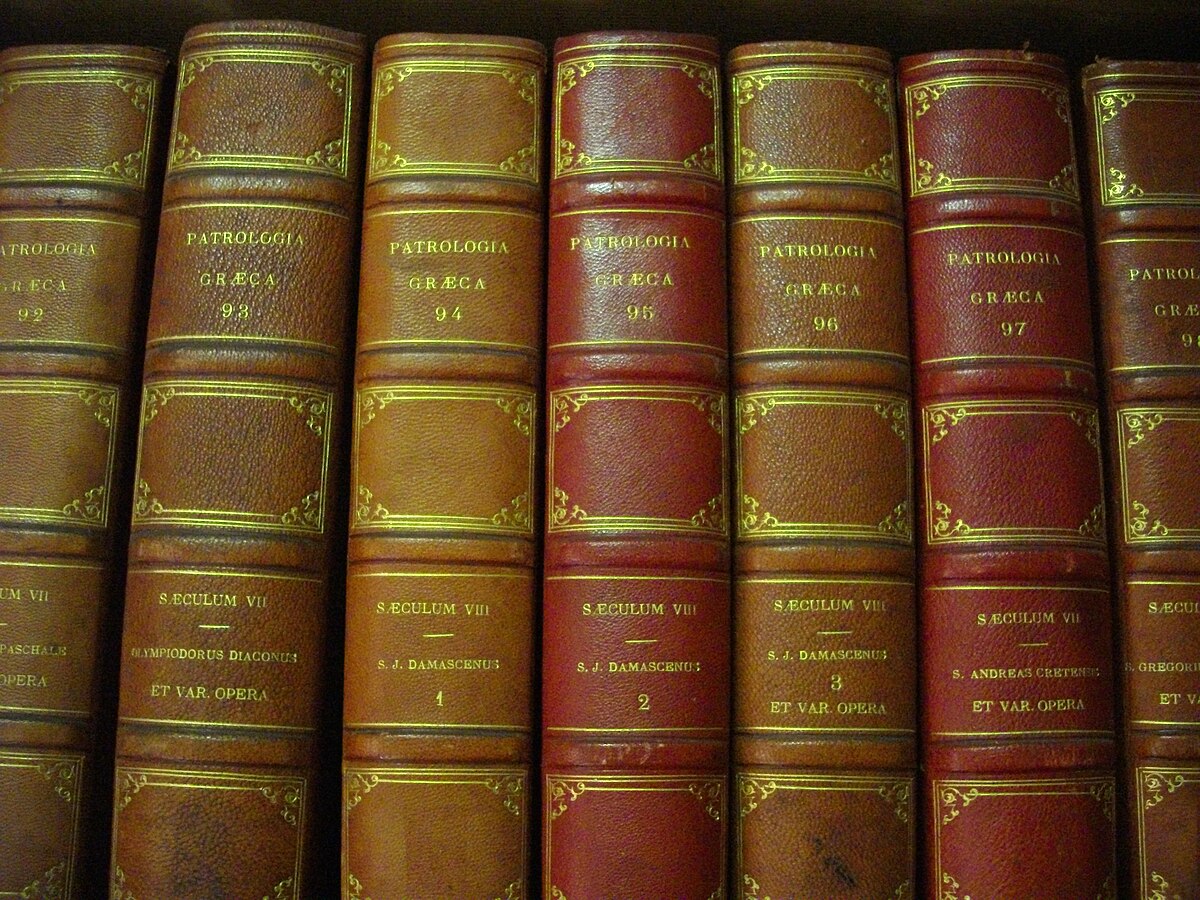

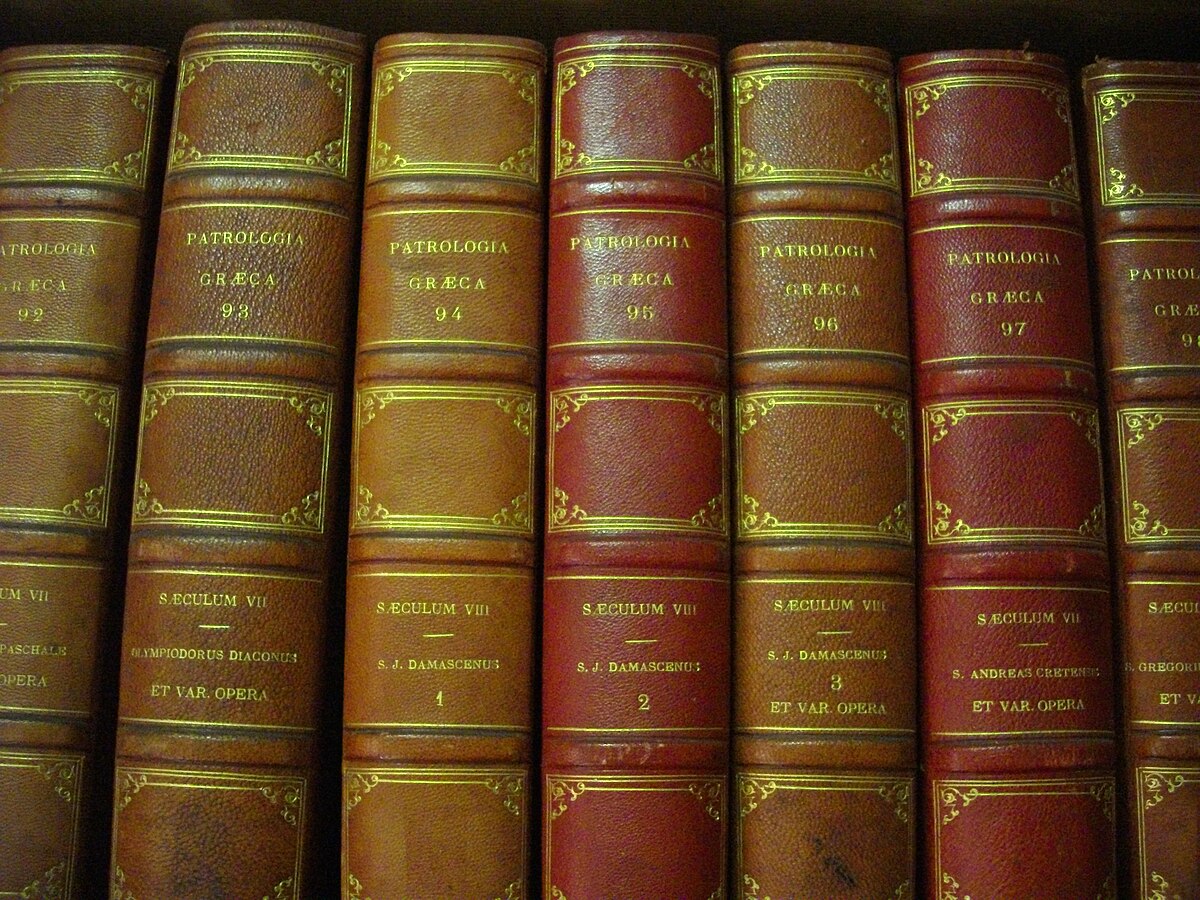

The Patrologia Graeca stands as one of the salient sources for the Scriptorium Project, as a large corpus of collected Byzantine documents. For the unfamiliar, the Patrologia Graeca (PG), was published by the French Jesuit scholar, Jacques-Paul Migne, between 1857 and 1866, and remains one of the most ambitious and influential attempts to collect the writings of the Greek Church Fathers in a single corpus. Comprising 161 volumes and covering the span of patristic literature from the Apostolic Fathers to the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the PG became the de facto reference for scholars working in theology, Church history, and Byzantine studies throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century. While it achieved immense reach and utility, the PG is deeply flawed in both its editorial approach and the underlying textual transmission it claims to represent. These issues include Migne's reliance on inferior manuscripts and outdated editions, the lack of critical apparatus, the haphazard integration of Byzantine scholia and commentaries, and an editorial methodology that prioritizes speed and accessibility over philological precision.

Migne’s editorial project must be understood within its proper historical context. His work was less a product of philological rigor and more of a commercial and ecclesiastical enterprise. As a French Catholic priest, Migne envisioned the Patrologia Latina and Patrologia Graeca as comprehensive resources that would support theological education and apologetics, especially in response to the challenges of Enlightenment rationalism and Protestant scholarship. Consequently, the PG was compiled not from autographed manuscripts or careful collation of variant readings, but from existing printed editions—many of which dated late, well beyond the original composition, to the 16th and 17th centuries and reflected the editorial standards of those periods. For example, the edition of Origen's Contra Celsum used by Migne was derived from the 17th-century edition by Hoeschel, which had already been surpassed in accuracy by the work of more recent editors by Migne’s time (Clark, 1992, pp. 3–7).

This reliance on outdated editions is especially frustrating for texts transmitted through complex Byzantine channels, many of which contain high levels of variance in their transmission. Byzantine monastic scribes, especially from the 9th century AD onward, played a crucial role in preserving patristic literature. Yet, they often altered texts through harmonization, interpolation, and doctrinal editorial correction. For instance, the transmission of Gregory of Nyssa’s works involves multiple recensions, especially regarding his anti-Apollinarian treatises, which were preserved in dogmatic florilegia that do not reflect the original composition (Silvas, 2007). Migne made no attempt to distinguish these layers of transmission, and in fact, in many cases, he reprinted Renaissance editions, that had been hurriedly carried out or Constantinople, and similarly conflated or smoothed over textual variants for doctrinal purposes.

A glaring weakness of the PG is the absence of a critical apparatus. Whereas modern editions, such as those published by the Sources Chrétiennes or the Corpus Christianorum, include extensive footnotes detailing variant manuscript readings, conjectural emendations, and editorial decisions, the PG provides virtually no such apparatus, saving only perhaps the terse introductions to the text. This is especially detrimental for authors whose texts survive in multiple Byzantine manuscripts with significant divergences. A prime example is the corpus of John of Damascus, whose theological and exegetical works exist in various recensions—some with Arabic intermediaries—yet the PG edition uncritically conflates these without commentary (Brière, 1952). The consequence is a misleading sense of authorial unity and coherence that obscures the actual dynamics of Byzantine textual transmission, which was often polyvalent and context-dependent.

Moreover, Migne’s treatment of Byzantine scholia and catenae introduces additional complications. Byzantine theological literature often involved the compilation of earlier patristic excerpts into chains of commentary (catenae), especially for biblical exegesis. These catenae sometimes preserve fragments of lost works, but they also commonly introduce pseudepigraphy and authorial misattribution. This is doubly present with the Patrologia Latina, wherein so many texts are attributed to the pen of St. Augustine. Migne's editions frequently incorporate these scholia into the body of texts without clear distinction. For example, in his edition of Theodoret of Cyrrhus’s Interpretatio in Psalmos, scholia from later Byzantine commentators such as Arethas or Euthymius Zigabenus are embedded alongside Theodoret’s own commentary, without clear delineation or attribution (PG 80). This editorial ambiguity contributes to confusion about the authorship and theological development of patristic exegesis across the centuries.

Furthermore, the homogenization of orthographic and syntactical features in Migne’s editions masks the historical and philological development of Byzantine Greek itself. Manuscript traditions from the 9th to the 14th century show significant variation in spelling, word division, and grammar, which can be critical in assessing the provenance and usage of particular theological terms. For example, the evolution of the term hypostasis in Trinitarian theology—central to figures like Maximus the Confessor—depends not only on its semantic field but also on how scribes understood and transmitted the term in relation to ousia and prosopon in various contexts (Thunberg, 1985). Migne’s editorial policy, however, regularizes such terms without comment, thereby flattening the nuanced theological debates that were shaped through scribal variation.

There is also the considerable matter of textual selection, which is perhaps the largest flaw within the collection. The PG is not exhaustive, nor does it follow a clear editorial principle for inclusion or exclusion. Migne chose to publish certain authors while omitting others whose works were less doctrinally central or more challenging to the French Catholic orthodoxy he wished to reinforce. This a priori selective canonization distorts the actual diversity of Byzantine theological and ascetical literature. Notably underrepresented are lesser-known Byzantine authors such as Symeon of Thessalonica or Nicholas Cabasilas, whose works have only recently received critical editions (e.g., Jugie, 1927; Mellas, 2003). Moreover, apocryphal, politically contrarian, and heterodox texts preserved in Byzantine manuscripts—important for understanding the full intellectual landscape—are absent from the PG, reinforcing a narrow ecclesiastical vision of orthodoxy. To this same point, Migne appears to ignore the ecclesiastical influence of the late Byzantine emperors, and we find that they are often left without a voice in his compilations. This is particularly salient with the emperors: Manual II, John VIII, and Constantine XI, who were heavily invested in the doctrinal integrity of their limited realm, and interacted with regularity with the Roman church.

Despite these limitations, Migne’s Patrologia Graeca continues to wield a surprising degree of influence, largely due to its accessibility and the sheer breadth of material it covers. In the absence of complete modern critical editions for many authors, the PG remains a necessary starting point, albeit one that must be used with caution. Scholars often use Migne’s text as a reference for locating passages, comparing later editions, or accessing hard-to-find Greek works. In digital humanities projects such as the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, many of Migne’s texts have been digitized and indexed, further cementing their role in contemporary scholarship, even as they are being critically reevaluated and, in many cases, supplanted. While the Patrologia Graeca represents an unparalleled effort to consolidate Greek patristic and Byzantine theological literature, its editorial shortcomings—stemming from a lack of critical engagement with manuscript traditions, an absence of textual apparatus, and a problematic treatment of Byzantine scholia—seriously limit its scholarly reliability. Migne’s corpus is best regarded not as a definitive textual repository but as a monumental, if flawed, artifact of 19th-century ecclesiastical publishing. Contemporary scholarship must continue the arduous work of producing critical editions grounded in careful manuscript collation and historical context, thereby recovering the richness and complexity of Byzantine Christian thought that the PG only partially, and often inaccurately, preserves.