MAY 2024

LEGACY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CONSTANTINOPLE

Written by: D. P. Curtin

Some years ago I was given a genealogical line of my own academic professors, being traced back through the centuries. In observing it, it was clear the path that high European civilization had drifted in the past millennia. In the last century it was largely composed of Anglo-Americans working within the university system. However, prior to this point, roughly prior to 1900, German scholarship was dominant, and the specializations of these academics was dispersed and at times comically sundry. Before that, around the time of the reformation, it moves south, into the ancient universities of central Italy and the coming of the Greek scholar Plethon, who triggered the Italian Renaissance with his appearance in the city of Florence, along with the retinue of the Emperor John VIII. It is in this earliest period that I observed the intellectual powerhouse of the Dark Ages and Medieval period, the now lost, University of Constantinople.

The University of Constantinople was established under imperial authority in the early Byzantine period, and represents one of the most significant yet paradoxically understudied institutions in the history of education. As the heir to the classical traditions of Hellenistic and Roman pedagogy, it exerted profound influence on the intellectual structures of medieval Europe, shaping the very template of university life long before the rise of Bologna or Paris, the oldest such institutions in Western Europe. At its height, it was a crucible of jurisprudence, philosophy, theology, and rhetoric, upheld by imperial patronage and integrated into the fabric of Byzantine governance and ideology. Yet despite its far-reaching intellectual legacy, the record of its later years is astonishingly meager, with the university vanishing from the historical record with little ceremony in the shadow of the Ottoman conquest of 1453. This lacuna underscores not only the fragility of institutional memory in Byzantium but also the deeper ironies of the empire’s cultural inheritance.

The foundation of the University of Constantinople is generally dated to 425 AD, during the reign of Theodosius II, who issued the relevant imperial edicts that established the Pandidakterion as a central organ of instruction in law, philosophy, and the liberal arts. This institution was a deliberate attempt to stabilize and Christianize the educational inheritance of Late Antiquity, while retaining the Greco-Roman curriculum that had once flourished in places like Alexandria and Athens. The Codex Theodosianus (14.9.3) lays out the faculty positions and subjects to be taught, including Latin and Greek grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy, with imperial funds dedicated to the maintenance of chairs and stipends. In this sense, the university was not merely a civic institution but a projection of imperial ideology—an instrument of orthodoxy, cultural hegemony, and the bureaucratic formation of the Eastern Roman State.

Its structure bore hallmarks that would reappear in later Western universities, including a fixed curriculum, hierarchical faculties, and state oversight of academic appointments. Indeed, the very concept of a university as a universitas magistrorum et scholarium, a guild of scholars authorized to confer degrees, draws on Byzantine precedents, albeit indirectly. The medieval Western university, while formally autonomous, emerged from cathedral schools and monastic learning environments that had been shaped by the Byzantine transmission of classical texts and methods. Figures such as Cassiodorus and Isidore of Seville, who laid the foundations for medieval Latin curricula, did so through engagement with Eastern sources that had been refined within the intellectual ecosystem of Imperial Constantinople. The Byzantine model emphasized the synthesis of rhetoric, dialectic, and philosophy with theological instruction—a model adopted with regional variations in the Latin West.

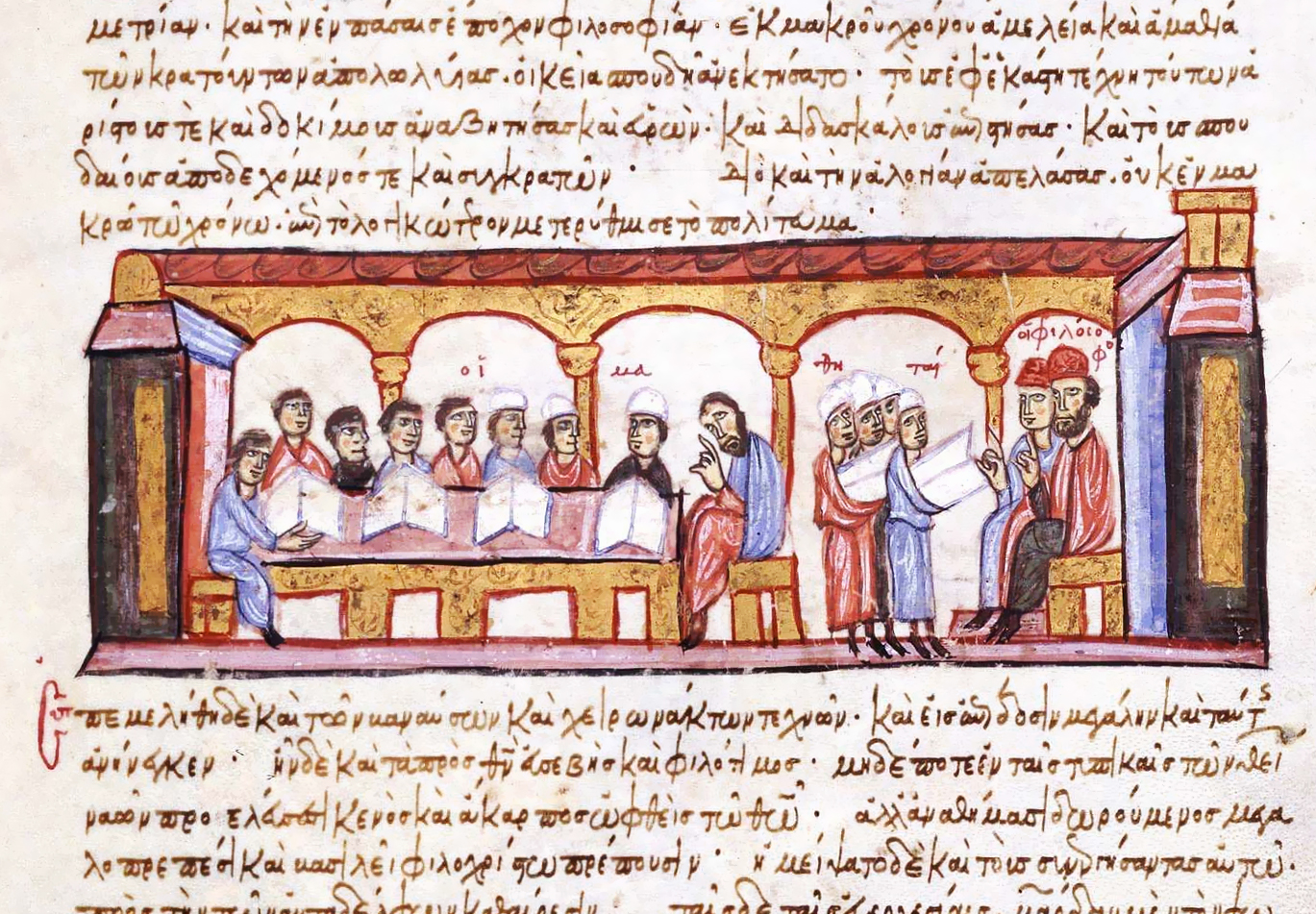

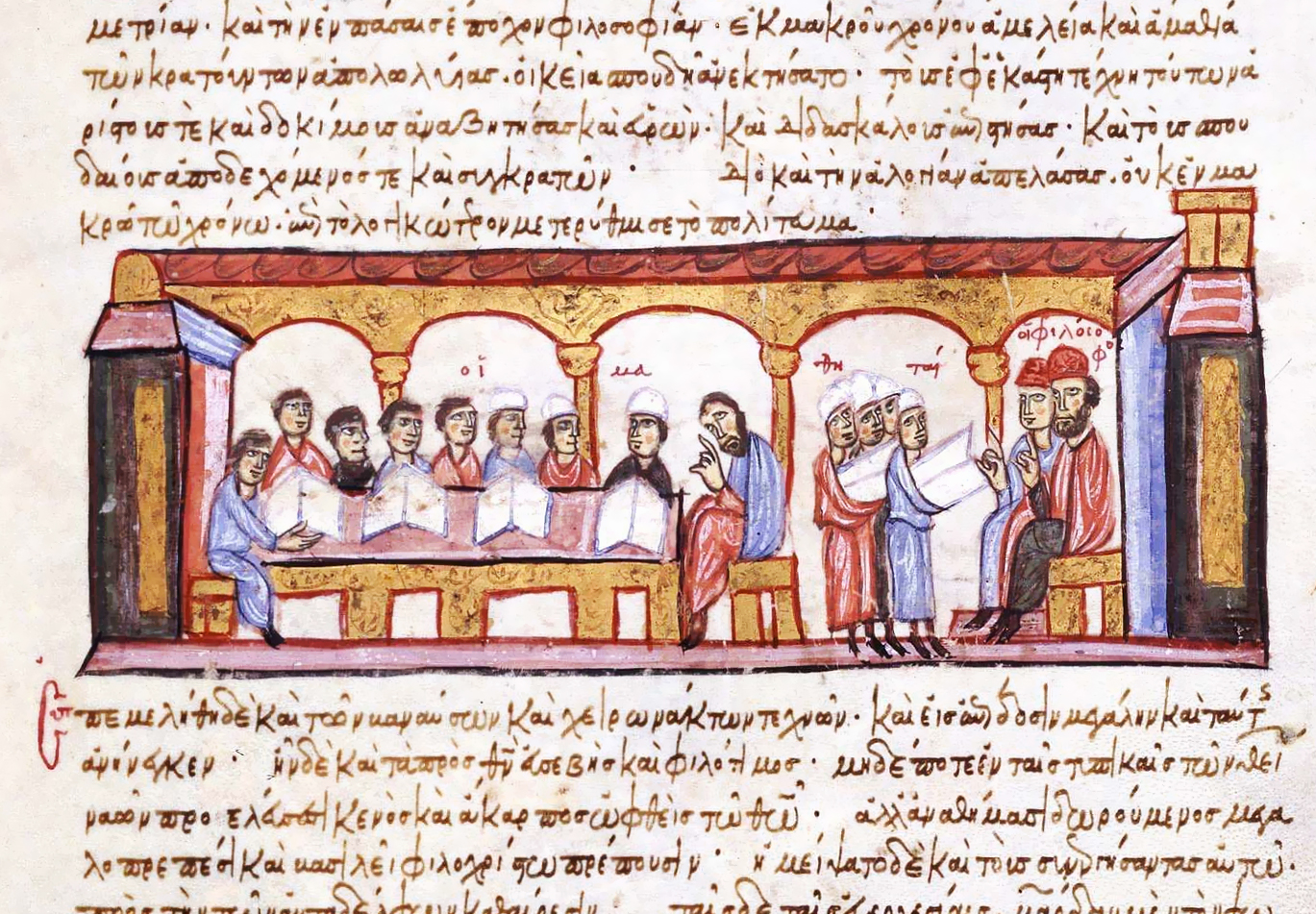

The height of the university’s influence can be located in the Macedonian and Komnenian periods, especially between the ninth and twelfth centuries, when emperors such as Basil I and Alexios I Komnenos invested significantly in the scholarly institutions of the capital. During this era, the university operated within a network of intellectual centers that included the Patriarchal School, the Monastery of Stoudios, and the court-sponsored scriptoria. While never wholly autonomous from ecclesiastical or imperial authority, it enjoyed a certain stability due to its strategic role in the cultivation of civil servants, judges, and theologians. Michael Psellos, a polymath of the eleventh century, was both a product and a reformer of this educational system, and his Chronographia offers vivid insight into the university’s intellectual climate, where Neoplatonism, Aristotelianism, and Christian doctrine coexisted in a delicate synthesis (Psellos, Chronographia, ed. Renauld, 1926). Psellos’ elevation of philosophy to a quasi-divine status influenced a generation of scholars, including John Italos, whose Aristotelian exegeses foreshadowed later scholastic developments in the West.

The imperial court viewed the university not merely as a center of learning but as a tool of cultural diplomacy and ideological control. Teaching positions were often filled by imperial decree, and scholars frequently served as envoys, rhetoricians, or theological polemicists. The rise of the Palaiologan dynasty in the thirteenth century, following the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–1261), witnessed a reinvigoration of classical learning under imperial sponsorship. The so-called "Palaiologan Renaissance" was not merely a literary movement but a strategic revival of Hellenic paideia, centered in part on the reconstructed educational apparatus of the capital. Scholars such as Maximos Planoudes and Demetrios Triklinios oversaw the collation and editing of classical texts, establishing philological methods that prefigured Renaissance humanism. Emperor Andronikos II even attempted to reestablish a structured educational system in Constantinople around 1300, appointing Theodore Metochites—renowned for his Neoplatonic learning and patronage of the Chora Monastery—as head of a new school attached to the Church of the Holy Apostles (Kaldellis, Hellenism in Byzantium, 2007).

This legacy was transmitted to the West not only through manuscripts but also through itinerant scholars. The emigration of Byzantine intellectuals, especially after the Council of Florence (1439), catalyzed the Italian Renaissance. Bessarion, Plethon, and Chrysoloras were all products of the Byzantine educational tradition, and they brought with them not merely texts but pedagogical techniques rooted in Constantinopolitan practice. Chrysoloras’ Latin grammar books and lectures in Florence and Venice essentially imported the curriculum of Constantinople into Italian soil, laying the foundation for the studia humanitatis. Thus, the intellectual DNA of Constantinople’s university survived even as the institution itself fell into obscurity.

Yet the final centuries of the university are shrouded in silence. While the intellectual life of the capital remained vigorous into the fifteenth century, there is little concrete evidence of a functioning university in the modern sense after the mid-fourteenth century. Surviving texts and correspondence suggest a shift from institutional to personal networks of instruction. The last known public lectures appear to have taken place under the auspices of individual scholars rather than any formal university. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the subsequent Ottoman policies toward Greek education meant that whatever institutional remnants remained were either absorbed into ecclesiastical structures or extinguished altogether. The absence of archives—no curriculum lists, administrative records, or faculty rolls—has rendered the reconstruction of the university's final phase almost impossible. What little survives is indirect: marginalia in manuscripts, letters between scholars, and Ottoman chronicles that note the end of the Christian "schools" in the capital.

The irony is sharp. An institution that helped lay the groundwork for European higher education ended in erasure. The Byzantine chroniclers—Doukas, Sphrantzes, Kritoboulos—barely mention the fate of the university during the fall of the city, focusing instead on the political and military drama. This silence is perhaps the clearest indication of the degree to which the university had ceased to function as a distinct entity. Its demise was not commemorated, perhaps not even noticed, amidst the wider cataclysm of imperial collapse. Unlike the University of Paris or Oxford, which kept meticulous records and produced self-sustaining traditions, the University of Constantinople left behind only scattered echoes of its former grandeur.

Attached below is the aforementioned academic genealogy, as far as I understand spanning back roughly to the turn of the last millennium.